KIMEP was established in 1992 when President Nazarbayev asked Dr. Chan Young Bang to form an Institute that would provide a western style higher education, using English as the language of instruction. The President’s strategic vision can be seen in the almost parallel establishment of the Bolashak scholarship program and, interestingly, both programs have each produced around 10,000 graduates who have made substantial contributions to the social and economic development of Kazakhstan.

KIMEP provides a high quality learning experience based upon best western practice.

Over 10% of students and 40% of academic staff are international. The University has over 100 international partnerships with universities in Europe, Asia, North America and elsewhere. Around a third of partners are ranked in the top 400 universities worldwide. There are 13 double degrees whereby students exchange between partners and receive two degree awards, one from KIMEP and the other from the partner institution. A further 4 dual degree programs are due to be established shortly.

The employment rate of our graduates is phenomenally high because, in all our programs, we aim to provide a student-centered learning experience in which the emphasis is upon what the students can do, not simply what they can remember. I think it is fair to say that KIMEP University has safeguarded the founding vision given to it by President Nazarbayev, 25 years ago.

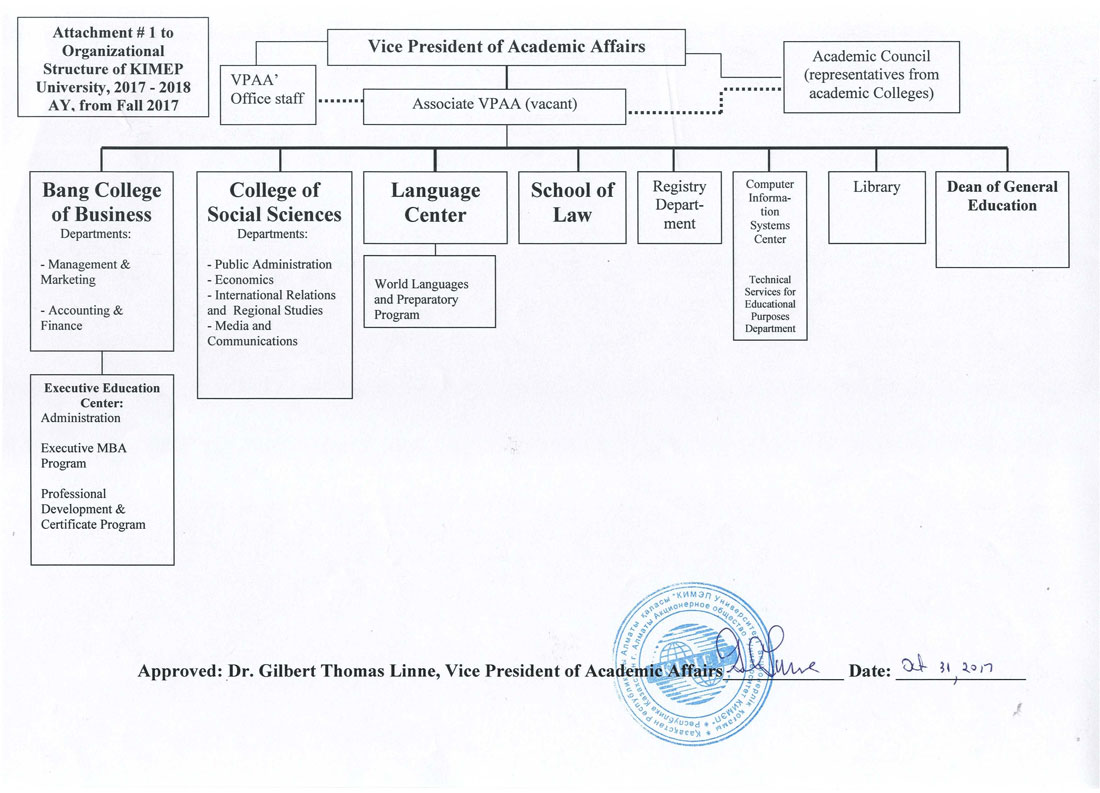

Organizational Structure of AA

Faculty Development and Support

FACULTY RESEARCH PUBLICATION AWARDS

These awards are given to recognize faculty achievements in scholarly publications.

APPLICATIONS FOR STUDY LEAVE

Granted for sabbatical study, research as unpaid leave. Requests for leave of absence for study leave should be reviewed at least 5 months before the leave begins.

CONFERENCE TRAVEL

Each college has funds available to support faculty who are presenting papers at conferences.

FACULTY TEACHING AWARD

The teaching excellence award recognizes inspanidual faculty members in each academic unit who are teaching in superior ways. Quality teaching assumes intellectual competence and integrity, creative pedagogical techniques that stimulate and direct student learning and critical thinking, provision of outside of class support for students, and the application of scholarly inquiry which results in constant revision of courses and curricula consistent with new knowledge which improves the learning experience.

FACULTY ANNUAL ACTIVITY AND MERIT REVIEW

Faculty Research

Faculty Research Resource (.doc)

Research Plan (.doc)

Research centers

- Bang College of Business (.doc)

- College of Social Sciences (.doc)

- Language Center (.doc)

- School of Law (.doc)

Evaluation of the Academic Degree Programs

In order to document and maintain high quality teaching and learning and to make improvements to study programs, the following on-going activities are maintained:

- A new faculty orientation program.

- Course revisions and proposals are reviewed by the University Curriculum Review, Accreditation and Admission and Scholarship Committee.

- Students participate in evaluation of academic programs every semester.

- Faculty guide and prepare formal and informal academic program review processes and documents.

- The Office of the Vice President of Academic Affairs (VPAA office) administers an internal award for innovation in teaching and learning.

- Academic Units and Administrative Offices that report to the Office of the Vice President of Academic Affairs prepare annual unit presentations and reporting to Academic Council that shows their goals, actions for improvement and responsible persons.

- VPAA office works closely with deans of the academic units to ensure that effective assessments are included in sponsorship funds and partnership agreements.

- The Office of Institutional Research collaborates with the VPAA office to generate and collect data, perform analysis and report results for decision-making about the instructors and courses in the academic program, deans’ activities and exit survey of graduates.

- VPAA office collaborates with the International Relations Office, the KIMEP Students’ Association and other campus groups to evaluate students’ campus experiences and off-campus study.

- Academic programs submit reports that describe course specific and student-centered learning outcomes, direct and indirect measures of student learning and future plans to improve student learning (Annual review of intended learning outcomes is available in Faculty Portal).

- VPAA office draws attention to faculty teaching practices through various means including peer observations by instructors, periodic news letters designed.

- Academic departments, programs and administrative offices that report to VPAA office participate in a five year cycle of external reviews and site visits, in-depth self studies and alumni surveys.

- Department and program assessment materials can be found on VPAA office webpage and information about student surveys can be found on the Office of Institutional Research webpage.

- Faculty and staff members who need assistance with survey construction or other assessment materials may contact the Office of Institutional Research for consultations.

FINAL ATTESTATION FOR GRADUATING STUDENTS

A. All undergraduate students choose one of the following final attestation options:

- a) Option 1:Pass Complex State Exam (1 credit) plus write/successfully defend a thesis (2 credits)

- b) Option 2:Pass Complex State Exam (1 credit) plus pass 2 additional state exams (1 credit for each exam) in major courses.

B. All masters and doctoral graduate students successfully complete and defend a thesis.

Teaching and Learning

1. A definition for critical thinking.

|

Reference:Klooster, D. (2001). What is Critical Thinking? Thinking Classroom/ Peremena Spring 2001 (4): 36-40.

Linked documents:–What is Critical Thinking?

|

|

|

|

2. Teaching a periphery course—a course that stretches our area of expertise.

|

References:Huston, T. (2010). Teaching what you don’t know. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(Loewenstein, G., Moore, D., Weber, R.A. (2006). Misperceiving the value of information in predicting the performance of others. Experimental Economics, 9, 281-295.) Linked documents:–Teaching outside your comfort zone |

|

|

|

3. Surveys of students’ views/Getting to know our students.Students define quality education here at KIMEP University according to the following key points:

One way of finding out about the students in our classes is to construct a short probe about what students already know about your class topic. List key terms or concepts related to your course and ask students what they know about them. You might provide five ways for students to respond: a) have never heard of this (key term or concept), b) have heard of it but don’t know what it means, c) have heard of it and could have explained in the past but forgot by now, d) recognize what it means and can explain in general, e) recognize what it means and can explain in some detail how it applies to the class. The list of key terms or concepts could include one to three terms per week or from each reading. Another ‘getting to know your students’ activity that would require just a few minutes is to use 3×5 cards or post-it notes to record some information about each student. Distribute the cards/post-it notes and ask students to write their names, contact information, major and responses to a general question such as, “What do you do?” Students may ask what the question means, but simply repeat the question and let students figure out how to respond. Some students may write about their jobs, others may write about how they spend their free time, interests, hobbies and so forth. Collect the student writing and look for connections between the students’ responses and the course topic(s). |

Reference:Kolowich, S. (2014) 5 things we know about college students in 2014. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 17 December 2014. Linked Documents:–5 Things we know about college students in 2014 |

|

|

|

4. Creating course environments that will foster active student learning.The course environments we create also raise questions about what our students know and what they can do and these questions can be useful for reflecting upon how we evaluate our students’ progress. A recent poll by the US firm Gallup in collaboration with Purdue University (2014) about student success after the university has raised some interesting ideas about student experiences during university study that could be useful for us here at KIMEP University. Four of the main factors during university study that contributed to student success are:

Instructors have a key role in creating course environments where student learning will be actively supported:

|

Reference:Michael, J. (2006). Where’s evidence that active learning works? Advances in Physiological Education, 30, 159-167. doi:10.1152/advan.00053.2006. Linked documents:–Where is the evidence the active learning works? |

|

|

|

5. Grading and evaluation of student work. Student evaluations of our teaching.A recent article (Levine, 2014) about grading practices raises questions about whether our current ways of evaluating student work actually encourage students to learn or to try to do their best work. A common method of evaluation is to assign points to each assignment so that students know how much each task is worth and how tasks fit into the larger picture of the course work as a whole. However, do points show us what students have learned? Do points raise student interest in learning more? Ways to use student course evaluations to improve our teaching: a) Reflecting on the teaching process in the course, |

References:Levine, M. (2014) Advocating a new way of grading. Retrieved from http://www.utimes.pitt.edu/?p=30598. University Times-University of Pittsburgh, 46, 18. Stark, P.B. and Freishtat, R. An evaluation of course evaluations. ScienceOpen Research 2014 (DOI: 10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-EDU.AOFRQA.v1) Linked Documents:–Advocating a new way of grading |

|

|

|

6.Small changes in our teaching practices to raise student learning.Seemingly insignificant adjustments in our communication with students, in our teaching practices and in our course design can influence our students’ learning in powerful ways. The series titled ‘Small changes in teaching’ provides several ideas for making small changes that can effectively boost your teaching and your students’ learning. |

Reference:Lang, J.M. (2015-2016). Series published in the Chronicle of Higher Education. Linked Documents:–A Strong ending semester |

|

|

|

7. Lecturing as a teaching practice.During a typical lecture format, the instructor is able to clarify ideas by talking through them; however, our role as instructors is not to teach ourselves, but to teach our students. This logic raises questions, then, about the role of our talk for our students’ thinking. While some discussions about student thinking advocate activities that promote more talk among students as a means of generating ideas, there are studies that question the role of talk as a means of thinking for all students from all cultural backgrounds. A previous study (Kim, 2002), for example, raised concerns about the role of student talk for thinking. “The Western assumption that talking is connected to thinking is not shared in the East. [This] research examines how the actual psychology of individuals reflects these different cultural assumptions. In Study 1, Asian Americans and European Americans thought aloud while solving reasoning problems. Talking impaired Asian Americans’ performance, but not that of European Americans. Study 2 showed that participants’ beliefs about talking and thinking are correlated with how talking affects performance, and suggested that cultural difference in modes of thinking can explain the difference in the effect of talking. Study 3 showed that talking impaired Asian Americans’ performance because they tend to use internal speech less than European Americans. Results illuminate the importance of cultural understanding of psychology for a multicultural society (p. 828). This study used the following questions to gain insight into talking and thinking relationships in educational settings: a. An articulate person is usually a good thinker. b. Eloquence does not have very much to do with intelligence. c. Talking clarifies one’s thoughts and ideas. d. Only in silence, can one have clear thoughts and ideas. Kim (2002) also raised the following implications, which may affect our interactions with our students: a) reconsider the influence of social-cultural background upon talking and thinking for our students (silence for example, can be considered as a culturally-positive trait for some students), b) even ‘basic’ cognitive functions such as verbal reasoning that seem universal for all people can be affected by social-cultural upbringing, c) mainstream principles for evaluation can be reviewed to see whether they focus primarily upon talking as a sign of thinking and adjustments made in our assessments for students who rely upon silence for thinking. The article is attached for your information and potential use in your teaching practices. |

Reference:Kim, H.S. (2002). We talk, therefore we think? A Cultural analysis of the effect of talking on thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83, 4: 828-842. Linked Documents: |

|

|

|

7. Using English in the classroom.Recent discussions recommend that instructors and their students learning English use English language at least 90% of the time including lectures, tasks and classroom management (Ceo-DiFrancesco, 2013). The main rationale for this recommendation is that “if learners do not receive exposure to the target language they cannot acquire it” (Ellis, 2005, p. 217). However, observations of instructors indicate that they resort to code switching, pop-up grammar (instances when instructors explain grammar using the students’ native language rather than the target language) and ‘periodic native language interventions’ to build rapport with students. Instructors use students’ native languages (L1) in the classroom in order to use time in particular ways, remind students of who is in charge and reduce uncertainty for students about target language meanings (Wilkerson, 2008). Concerning time, “instructors use [native language] to control the speed of classroom interactions activities, eliminate waiting or lag time and limit turn taking by students” (p. 316). Concerning the need to assert authority in the classroom, instructors use students’ native languages to maintain control of student behavior and limit time needed to complete sequences of interaction. Concerning the need to reduce uncertainty, instructors use the students’ L1 to make sure that students understand what is being communicated. However, instructors’ uses of L1 to control interactions, reduce waiting time, and maintain control of students’ behaviors can have the unintended consequence of limiting students’ opportunities to communicate in the target language. Acquiring English as a foreign language requires extensive, understandable use. The following ideas are suggested for instructors in building students’ understandings about English during their coursework:

|

References:Ceo-Di Francesco, D. (2013). Instructor target language use in today’s world language classrooms. Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. Retrieved from www.csctfl.org/documents/2013Report/Chapter%201.pdf Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. System, 33, 209-224. Wilkerson, C. (2008). Instructors’ use of English the modern language classroom. Foreign Language Annals, 41, 2, 310-319. Linked Documents:–Instructors’ use of English in the modern language classroom |

|

|

|

8. Course design.In designing a course, we may begin by looking at the course syllabus of the previous instructor. We might look at the course calendar and give immediate attention to arranging the readings, deciding how many exams to give, and figuring out how many homework assignments or projects to give, and when. Then we may review the course objectives and the intended learning outcomes. Huston (2010) explains that this approach tends to focus on filling the class meeting times and covering course topics rather than on supporting students’ deeper understandings about the course topics and concepts. An alternative approach, which Huston (2010) suggests, is to give attention first to what we want students to do. For example, in a marketing course, one outcome might be to “demonstrate competence related to marketing”. The next step in this alternative approach to planning would be to list the kinds of evidence that would show competence related to marketing. As we consider the kinds of evidence we are looking for, we might also give some thought to what students would do with the evidence that would count as exceptionally good performance or good performance or adequate performance or minimally acceptable performance or failing performance and to briefly describe those performances. The third step would be to decide what activities we will do and what activities students will do in order to produce the kinds of evidence we are looking for. Last, we could organize the calendar and the assignments to support the activities we do and the students will do. This alternative approach focuses less on the calendar at first and more on the connections between student performance, course activities and course concepts. This alternative approach can help students learn more about the course concepts and it can help us as instructors by focusing on what activities need to be done during the course, which evidence we and the students will give attention to and what assignments really matter for the course. |

Reference:Huston, T. (2010). Teaching what you don’t know. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. |

|

|

|

9.How faculty guide their interactions with students to raise student academic achievement.A recent research article (Ottmar, Rimm-Kaufman, Larsen & Berry 2015) explains that raising student learning results from the quality of teacher-student interactions, instructional tasks and opportunities for students available in the setting. The primary guiding questions for the researchers were: a) what occurs inside of classrooms and b) how do teacher strengths and context factors improve teaching practices that can raise student learning? Although this article focuses on elementary and secondary teachers and students, similar questions and concerns can be raised for university teaching and learning. Prior research has proposed that social and emotional interventions can help students to interact positively “and develop self-management skills necessary for learning” (p. 789). During teacher-student interaction, teachers must evaluate moment-by-moment student understanding of concepts based upon student answers. Teachers must also anticipate what information to introduce next. More successful teachers are able to bring together their knowledge of the subject content with awareness of student understanding and use appropriate models and representations of concepts during instruction. “The teacher carries out complex analytic work, estimating what students know and what they do not know, discovering particular identities of their students and their problems, finding and repairing what becomes problematic in the [students’ responses], steering the discourse in particular directions and exploring alternative interactional trajectories in the course of action (Lee, 2007, p. 1226). In summary, this research suggests that it is important to give close attention to our feedback to students’ comments and questions. Our feedback to students reveals how we analyze what students know, what they do not know, what problems they encounter, and our decisions about what directions we chose for students to take through course material and concepts. |

References:Lee, Y-A (2007). Third turn position in teacher talk: Contingency and the work of teaching. Journal of Pragmatics, 39, 1204-1230. Ottmar, E.R., Rimm-Kaufman, S.E., Larsen, R.A., and Berry, R.Q. (2015). Mathematical knowledge for teaching: Standards-based mathematics teaching practices and student achievement in the context of the Responsive Classroom Approach. American Educational Research Journal, 52, 4, 787-821. |